The expedition of Bjorling and Carstenius is one of the least known of the Arctic expeditions.

This limited-budget expedition was the type of expedition that many young adventurers dream of, but few dare to undertake. It came to a tragic end just a few months after it started.

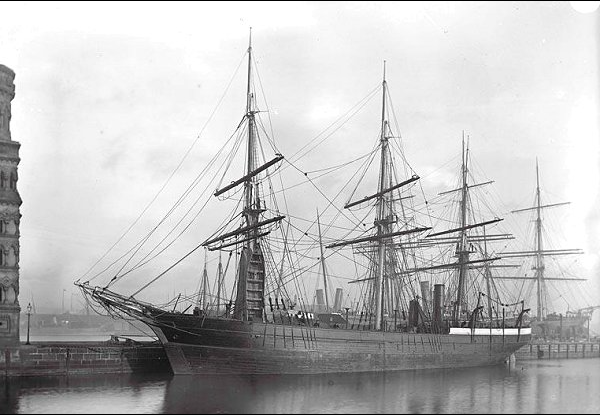

Johann Alfred Bjorling disappeared during an expedition to the high Arctic in 1892-1893. (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Johan Alfred Bjorling was a Swedish botanist who set out on his fateful expedition in 1892 at just 21 years old. However, he had already built quite a reputation.

Two years ago, he was on an expedition to Spitsbergen as a botanist. The following year, he attempted the impossible journey from Godhavn (now Kekertalsuaq) in Greenland to Melville Bay by rowboat.

His northernmost acquisition that year was Devil’s Thumb (Karasuaq in Greenlandic), a famous landmark for whalers at the southern end of Melville Bay.

In 1892 he decided to carry out a botanical survey of Ellesmere Island. His companion is Evald Karstenius, a 24-year-old zoologist and fellow Swede.

The scientists and adventurers first headed to St. John’s Island, where they purchased a small 37-ton schooner, the Ripple, for $665. They hired a 21-year-old Danish man as captain and two local men as crew members.

They brought this small ship through the treacherous ice to Godhavn within a month. The plan was to explore Ellesmere Island in the summer and return to Godhavn as soon as the autumn.

Unfortunately, nothing went as planned.

The expedition left Godhavn on 2 August 1892 and crossed Melville Bay. They continued north to the eastern tip of the Cary Islands, small islands off the coast of northern Greenland, southwest of the present-day community of Karnak.

In 1875, George Nares, leader of the British Expedition, stashed supplies there, and Bjorling intended to use them.

Shortly before August 17, after the group loaded the Ripple with provisions from caches in Britain, the ship ran aground, probably due to the pressure of ice floes.

Undaunted, Bjorling and his companions attempted to sail north to Folkefjord in the boat of the ship they had purchased in Godhavn, but failed and returned to the site of the wreck.

Stranded on the Carey Islands with no way to get south, and with winter arriving and daylight hours significantly reduced, the next step is to take a boat to the Green, which is clearly visible and only about 40 miles away. It would have made sense to head for the Rand coast. Away.

There they almost certainly would have met Dogwhit. Dogwhit could have survived the winter. In fact, before leaving Godhavn that summer, Bjorling wrote, “If I need to overwinter, I will rely on the Eskimos of North Greenland or the Danes on the West Coast.”

When Bjorling wrote these words, he did not expect that his plans to reach Ellesmere Island would be thwarted by a shipwreck. And he was a man known for his determination and stubbornness. He was more determined than ever to visit Ellesmere Island.

In his last message left on the Carey Islands, he wrote: I hope that a whaling ship will visit Cary Island next summer and rescue me and my companions, so I will try my best to reach the island again by July 1st. ”

He added: “We have five people now, and one of them has died.”

The memo was dated October 12, 1892.

After that, the expedition, missing one person, disappeared to the west, leaving four people in a small boat vainly headed for the unknown Ellesmere Island. I never heard from them again.

Did they work? No trace of them or their small craft has been found on Canadian shores. If they had gotten there, they would surely have perished. Because there were no Inuit living on that coast to help them. Instead, they almost certainly ended up in a watery grave in the frigid depths of Smith Strait.

In June of the following year, Captain Harry Mackay of the Scottish whaler Aurora discovered the shipwreck at the easternmost tip of the Cary Islands. He lands and finds Ripple buried in winter snow and ice. The body of a man was found buried under a pile of stones nearby. McKay quickly gathered up any artifacts he could find, including Bjorling’s last message.

Among the items recovered by McKay were several pages of the book Bjorling had taken with him on his ill-fated expedition.The book is 3 years of Arctic activitiesby A. W. Greeley, who starved many people to death on Ellesmere Beach ten years ago.

One wonders if Bjorling bothered to read it. If so, it becomes increasingly puzzling why they headed for Ellesmere rather than the more accessible Greenland coast.

Swedish zoologist and explorer Axel Ohlin accompanied the whaler Eclipse in 1894 on a promising but unsuccessful rescue mission.

Back home in Sweden, the families of the two young scientists were grieving their deaths.

Their mourning was made a little easier by the fact that fellow Swedish polar explorer AE Nordenskjöld, even before the fate of the young men was known, bluntly stated in a letter to the Karstenius family: It never happened. must accept the dangerous consequences of their actions. ”

One Swede summed up the tragic death of Bjorling, and by extension Carstenius, when he wrote: Equipped. ”

Taissumani is an occasional column recalling events of historical interest. Ken Harper is a historian and author who lived in the North Pole for over 50 years. He is the author of books such as “Minik: The New York Eskimo” and “Thou Shalt Do No Murder.” feedback? Send comments or questions to kennharper@hotmail.com.