The first time Dr. Peter Hackett sees a patient with frostbite, the man dies from his wounds. It was Chicago in 1971, and the man got drunk and passed out in the snow, his fingers freezing so badly that gangrene eventually set in.

Hackett went on to work at Mount Everest Base Camp in Denali, Alaska, and now works in Colorado, where he became an expert in treating cold-weather injuries. His experiences were often the same. There wasn’t much that could be done about frostbite other than keep the patient warm, give aspirin, and in severe cases, amputation. And, in many cases, they waited, accepting that after six months the patient’s body might “auto-amputate.” Allow dead fingers and toes to fall off naturally.

Hackett, a clinical professor at the Center for Advanced Research at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, recalled a leader in Anchorage, Alaska, saying, “January is frostbite, July is amputation.” “For centuries there was nothing else to do.”

This month, the Food and Drug Administration approved the nation’s first treatment for severe frostbite. The drug iloprost is given intravenously several hours a day for a little over a week. It works by opening blood vessels to improve circulation, reduce inflammation, and stop the formation of platelet clumps that can shut down circulation and destroy tissue. Most at risk are a person’s toes, fingers, ears, cheeks, and nose.

Approval of this treatment is as much a scientific novelty as it is a moneymaker for the pharmaceutical industry.

Experts say there is not enough data on how many people are suffering from frostbite severe enough to receive this treatment. However, the number of cases in the U.S. may only be a few dozen per year, said Dr. Norman Stockbridge, chief of the Division of Cardiology and Nephrology at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, which approved the drug.

“If you look at people who are really at risk of getting frostbite and really losing their numbers, that’s pretty rare,” Stockbridge says. Still, “it’s better to have medicine than nothing.”

Indeed, the approval of a drug to treat frostbite highlights the unspoken reality of severe injury. That’s rare.

Those most at risk are high-altitude climbers, people working outdoors without proper equipment, homeless people, and especially people with poor circulation.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, frostbite occurs at “extremely low temperatures,” and frostbite often occurs when blood vessels are damaged by blood clots or inflammation during the thawing process, resulting in stagnation of blood flow.

About two-thirds of all frostbite cases involve a mild form known as frostnip, which makes them unlikely candidates for the drug, said Alison Widlitz, vice president of medical affairs at Eikos Sciences, a San Mateo, Calif., startup. . That the FDA has approved the drug for sale. She estimated that the U.S. market for iloprost would be fewer than 1,000 people a year.

“Although the market is small, this is an important new option,” she said. Widlitz said Eikos, which has seven employees, has not yet set a price for the drug.

Many injection treatments for these rare conditions are very expensive. Treatment with iloprost involves infusion for 6 hours a day for up to 8 days.

Widlitz added that the company was founded to explore drugs to address iloprost and other unmet medical needs.

This is not the first time this drug has been used. The inhaled version of iloprost was first approved by the FDA in 2004 as a treatment for pulmonary hypertension. After French physician Dr. Emmanuel Cauchy showed it to be effective in treating frostbitten climbers, his IV version has been approved for severe frostbite in many European countries over the past decade.

His study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011, found that of the 16 frostbitten patients who were given the drug, those in the study faced the risk of amputation due to their injuries. It turned out that there was no one. The study showed that 9 out of 15 other patients who did not receive the drug were at risk.

A subsequent study, published last year in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health, a publication dedicated to health issues affecting people living in the Arctic, found similar results. The report noted that use of iloprost “demonstrated a reduction in amputation rates compared to untreated patients.”

As an example, a 2018 paper published in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine investigated treatment of five Himalayan climbers with iloprost and found that the drug prevented tissue loss in two of them and reduced tissue loss in two others. was found to be restricted. These case studies found that the drug was effective when administered 48 to 72 hours after the onset of critical wrinkles, as climbers often do not receive treatment immediately.

If frostbite is detected more quickly, a stroke treatment drug called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) can be used to limit blood clot formation and reduce the risk of amputation. However, if the drug is not given within a few hours, it can lead to serious complications and death. Unlike iloprost, tPA is not approved by the FDA for severe frostbite, but doctors are using it off-label.

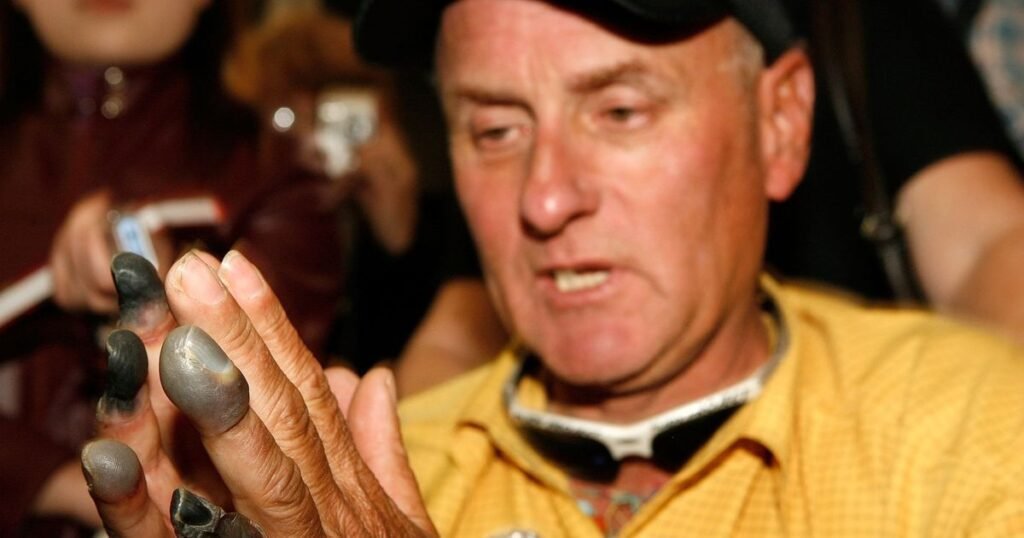

Hackett said the world of people suffering from severe frostbite includes people who work in extremely cold environments, such as “climbers, stranded snowmobiles, mountain climbers, the military,” as well as people who are homeless and have “drug and alcohol problems.” This includes people who are at risk and are at risk. Cold for a long time. ”

Jennifer Rybovich, a homeless Boulder, Colorado resident, suffered from severe frostbite on a frigid night in December 2016.

She remembered that she had been drinking heavily and that the weather had been nice the day before. “The next day I woke up and it was covered in snow. Her shoe had fallen off while she was sleeping. Maybe I kicked her. It stuck me to the ground.”

“As I kept walking, I could tell that my legs felt different, but I just thought it was cold,” she said. Five days later, she went to a detox unit, where she “experienced excruciating pain” as her body warmed up and her legs unraveled.

The thaw stage is when damage begins and capillaries deteriorate, sometimes becoming irreparable. “Different parts of her legs changed from black to light blue,” she said.

At the doctor’s appointment, she soaked her foot in warm water, elevated her foot, and placed gauze between her toes to keep the rejuvenated skin cells from merging. Some of her skin fell off and all of her toenails were missing. When the doctors were finally satisfied that the foot had healed as well as possible, “they shaved a quarter inch of my big toe – they called it ‘shaved.’ I shaved it,” she said.

The shaving occurred in the summer, roughly matching the six-month timeline of Hackett’s mentor’s adage of injury in early winter and amputation by summer.

So while the market for a new drug may be small, Hackett expects it could lead to savings in the orders of magnitude.

“It’s wonderful,” he said. “The old adage may change.”

This article was first published new york times.