There’s nothing quite like the late-night charm of a colorful comet orbiting the sun. But it is undoubtedly the ugly ducklings of ancient asteroids that explain how our solar system evolved from a giant gas and dust giant to the proto-solar nebula that gave birth to our burning hydrogen sun. It gives us a deeper understanding. Incredibly diverse planets soon followed, including Earth.

Asteroids may not be the sexiest objects in the solar system. But in many ways, we are a byproduct of the asteroid. That’s because asteroids likely provided prebiotic molecular precursors to large amounts of Earth’s water and the rich chemicals from which we evolved.

However, until the 1990s, little was known about its composition and diversity. But over the past decade or so, laboratory studies, space missions, and ground-based observations are rewriting the record about the debris left behind when the solar system formed some 4.56 billion years ago. .

In other words, the SPHERE (Spectropolarimetry High Contrast Exoplanet Research) instrument currently in operation at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope has already succeeded in making detailed observations of 42 of the largest objects in the asteroid belt.

Although this SPHERE instrument was developed to study planets around other stars, our team is using it to study the shapes of asteroids, and planets researchers at the European Southern Observatory Astronomer Michael Marcet told me at ESO’s offices in Santiago. If you can measure its shape as it rotates, you can measure its volume, and if you have an estimate of its mass, you can measure its bulk density, he says. This is important evidence for understanding their internal makeup, he points out.

Get the most out of high-resolution images

I’m interested in all populations of small objects in our solar system, from a few meters to a few kilometers, Marcet says. And for the first time, he says, thanks to a new generation of instruments like the SPHERE instrument, it is now possible to resolve these objects across hundreds of photographic pixels.

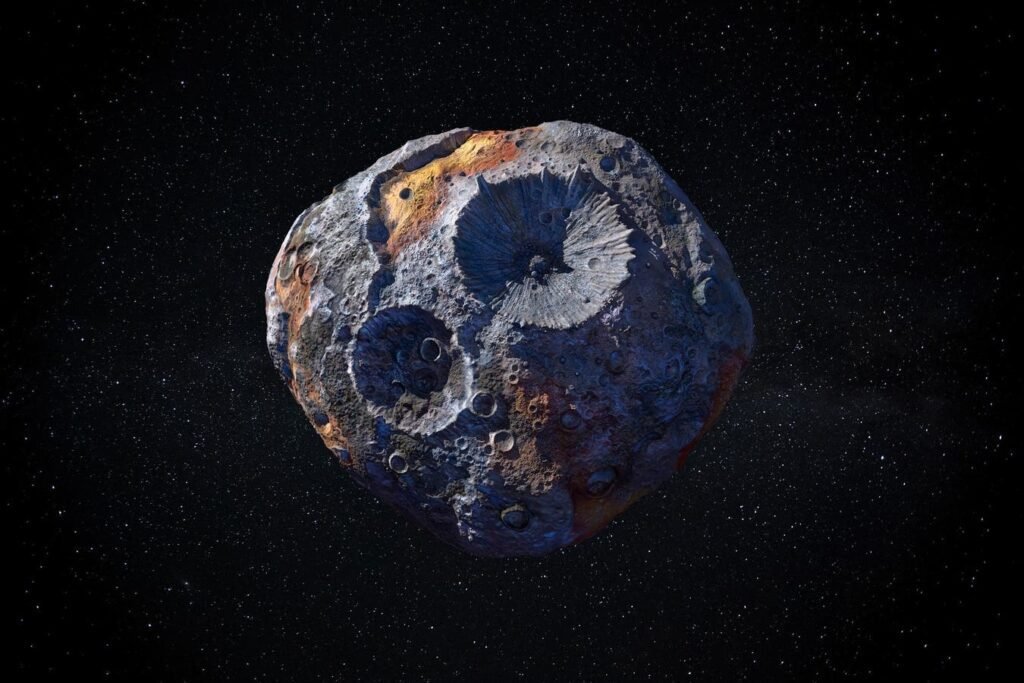

Marcet said SPHERE can also image geological features on the asteroid’s surface.

Marcet et al. found that the density distribution of asteroids in the main asteroid belt is bimodal, with about half of the objects having a density similar to that of silicates. The other half is thought to contain a significant portion of lighter, more volatile chemical species, such as water ice.

This means that perhaps as many as half of the objects now in the main asteroid belt (located between Mars and Jupiter) did not form in situ, but rather accreted further afield, Marcet said. To tell.

Some of them may even have originated in the toroidal Kuiper Belt, a circumstellar region of icy objects found outside Neptune’s orbit. Even if some of these asteroids originated far outside the Kuiper belt, the exact timing of how they were hurled into their current orbits is still unknown. However, this is thought to involve Jupiter moving inward and Neptune moving outward.

Making connections from meteorites to asteroids

Marcet said the asteroid is exposed to solar wind, micrometeoroid impacts, and all sorts of physical processes that can change its spectral properties. Establishing a connection between laboratory and astronomical measurements therefore requires a better understanding of these processes and how solar radiation cooks the asteroid’s surface, he said. say.

Most of what we know about protoplanetary disks comes from laboratory studies of meteorites and interplanetary dust particles. But it is the chemical and isotopic composition of meteorites that tells us what thermal and chemical conditions prevailed before our planet was fully formed.

Still, astronomical observations are needed to link laboratory measurements to specific locations in the solar system, Marcet said. By linking these meteorites to specific locations, he says, we can learn where these processes occurred in the protoplanetary disk.

The answers require continued research both on Earth and in space.

Marcet says it’s an open question whether Earth’s diversity of complex organic molecules was formed during Earth’s early chemical evolution or came from other celestial bodies. I really want to understand how these asteroids contributed to the emergence of life on Earth, he says.

ESO’s ELT can help

ESO’s upcoming Very Large Telescope will study main-belt asteroids up to 35km in diameter and craters around 10km in size, ESO said.

What surprised Marcet most about these small objects?

Incredible diversity at all levels of these objects. Each is its own world, Marcet says, with its own story to tell about our solar system. Some revolve around the sun in simple round orbits. Some people, he says, are doing a frenzied dance with Jupiter and Neptune. But as we measure these objects every night, he points out, we are increasing our understanding of how the solar system evolved into its current structure.

follow me twitter or linkedin. check out my Website or my other works here.