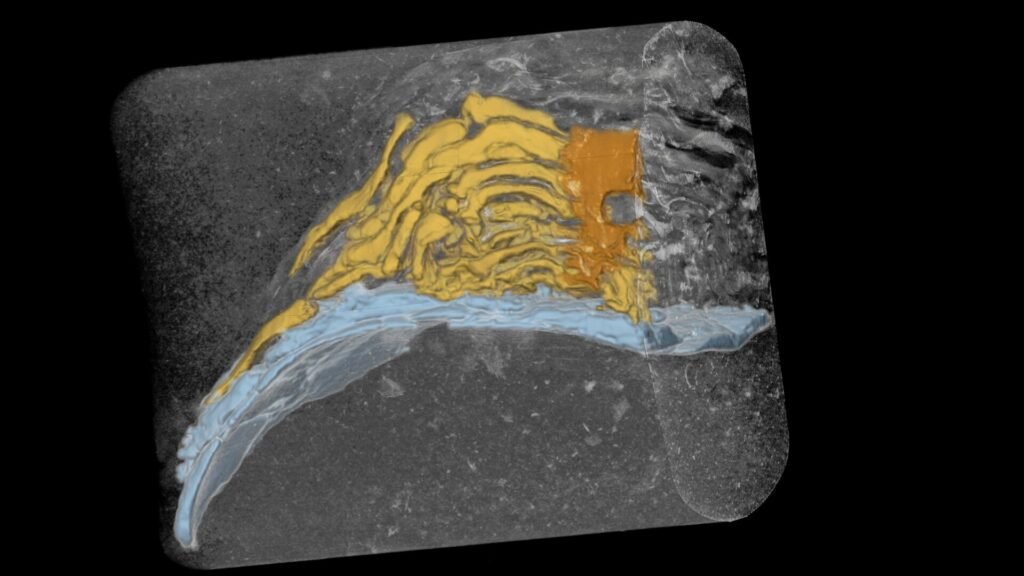

X-ray reconstruction of a 32-million-year-old fossil kelp holdfast. It is color-coded to indicate the base (orange), the holdfast (yellow), and the bivalve shell to which it was attached (blue).Credit: Dula Parkinson/Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

× close

X-ray reconstruction of a 32-million-year-old fossil kelp holdfast. It is color-coded to indicate the base (orange), the holdfast (yellow), and the bivalve shell to which it was attached (blue).Credit: Dula Parkinson/Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

The unique underwater kelp forests that line the Pacific coast support a diverse ecosystem that is thought to have evolved with kelp over the past 14 million years.

But new research shows that kelp flourished off the northwest coast more than 32 million years ago, long before the modern groups of marine mammals, sea urchins, birds and bivalves that call forests home today. Ta.

These coastal kelp forests are now rich ecosystems that support otters, sea lions, and seals, as well as many birds, fish, and crustaceans, and are much older than ancient and now extinct trees. This means that it was likely the main food source for these mammals. Called Desmostyrian. The hippopotamus-sized herbivore is thought to be related to today’s sea cows, manatees, and their terrestrial relatives, elephants.

“People initially thought, “There were no organisms associated with modern kelp forests yet, so kelp was growing before 14 million years ago,” said Cindy Louie, a paleobotanist and professor of integrative biology at the University of California. I don’t believe it didn’t exist.” , Berkeley.

“Now we show that the kelps were there. It’s just that all the organisms you’d expect to be associated with them weren’t there. This is not so strange. Not because we need the foundation of the whole system first before everything else comes along.”

Evidence of the antiquity of kelp forests reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencescomes from newly discovered fossilized kelp roots, the root-like parts that anchor kelp to rocks and rock-bound organisms on the ocean floor. The handle or stem is attached to the holdfast and supports the blade, which normally floats in the water thanks to an air bladder.

Loey’s colleague Steffen Kiel dated these fossilized scaffolds, which still hold shellfish and encased barnacles and snails, to 32.1 million years ago, during the mid-Cenozoic era, which lasts from 66 million years ago to the present day. estimated that. The oldest known kelp fossil to date, consisting of one swim bladder and one blade similar to today’s cow kelp, is 14 million years old and is housed at the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) It is held in.

A slice of a 32-million-year-old fossilized sessile showing a finger-like octoptera growing on a barnacle.Credit: Stefan Kiel

× close

A slice of a 32-million-year-old fossilized sessile showing a finger-like octoptera growing on a barnacle.Credit: Stefan Kiel

“Our evidence provides good evidence that kelp is a food source for the enigmatic marine mammal Desmostilia,” said Kiel, lead author of the paper and senior curator at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. Stated.

“This is the only Cenozoic mammal that actually went extinct during the Cenozoic Era. Kelp has long been suggested as a food source for these hippopotamus-sized marine mammals, but actual evidence is lacking. Our solid evidence shows that kelp is a strong candidate.”

These early kelp forests may not have been as complex as the forests that evolved by about 14 million years ago, said Keel and Louie, lead authors of the paper and curator of paleobotany at UCMP. is said to be high. Late Cenozoic fossils along the Pacific coast include clams, oysters, mussels and other bivalves, birds, and marine species, including the sirenian, a relative of the manatee and the extinct bear-like sea otter predecessor called colponomos. This indicates the abundance of resident mammals. Such diversity is not seen in the fossil record from 32 million years ago.

“Another implication is that the fossil record once again shows that the evolution of life, in this case the evolution of kelp forests, was more complex than would be inferred from biological data alone,” Keel said. he said. “The fossil record shows that large numbers of animals appeared and disappeared from kelp forests over the past 32 million years, and that the kelp forest ecosystems we know today evolved only in the past few hundred years. It shows that it will last forever.”

Value for fossil hunting amateurs

The fossil was discovered by James Goedert, an amateur fossil collector who has worked with Keel in the past. When Goedert broke down four stone nodules he found along the shore near Jansen Creek on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, he thought they were like clumps of kelp and other macroalgae that are common along the coast today. I saw what I could see.

Keel, who specializes in invertebrate evolution, agreed, and then dated the rocks based on the ratio of strontium isotopes. He also analyzed oxygen isotope levels in the bivalve shells and confirmed that holdfasts lived in slightly warmer waters than today, at the upper end of temperatures found in modern kelp forests.

This timeline depicts the evolution of Pacific Coast kelp forests and associated organisms over the past 32 million years as water temperatures change. The black bars represent members of the complex modern kelp ecosystem, including sea otters, abalone, sea urchins, and, until recently, sea cows. Green bars indicate early, now extinct members of the kelp formation, such as desmostyrians and penguin-like protopterids. Credit: Steffen Kiel and Cindy Looy

× close

This timeline depicts the evolution of Pacific Coast kelp forests and associated organisms over the past 32 million years as water temperatures change. The black bars represent members of the complex modern kelp ecosystem, including sea otters, abalone, sea urchins, and, until recently, sea cows. Green bars indicate early, now extinct members of the kelp formation, such as desmostyrians and penguin-like protopterids. Credit: Steffen Kiel and Cindy Looy

Louie contacted his co-author, Dula Parkinson, an advanced light source scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who used synchrotron radiation I asked for assistance in obtaining one 3D X-ray scan. . When she reviewed her detailed X-ray slice of the fossil, she saw that in addition to the bivalve it was riding on, there were barnacles, snails, mussels, and small unicellular foraminifera hidden inside the holdfast. She was surprised when she saw it.

However, Louie pointed out that the invertebrate diversity found within the 32-million-year-old fossilized fort was not as high as that found within today’s kelp forts.

“The holdfast is nowhere near as rich as it would be if you went to the kelp ecosystem right now,” Louie said. “The organisms living in these ecosystems had not yet begun to diversify.”

Keel and Louie plan further study of the fossils to see what they reveal about the evolution of the North Pacific kelp ecosystem and how it relates to changes in the ocean climate system. .

Other co-authors on the paper are algae expert Rosemary Romero, a Ph.D. She received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 2018 and is currently an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Michael Krings, a paleobotanist at Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich, Germany; and former University of California, Berkeley undergraduate student Tony Hein. Goedert is a research fellow at the University of Washington’s Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle.

For more information:

Kiel, Steffen et al., Colonization of kelp in the early Oligocene and gradual evolution of kelp ecosystems in the North Pacific, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2317054121. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2317054121

Magazine information:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences