Prime Minister Justin Trudeau caused a stir on Wednesday by turning what began as a review of the government’s response to foreign interference into a sharp criticism of Conservative Party leader Pierre Poièvre.

“I’m getting more partisan than I intended in this case, but it’s true that the leader of the government’s opposition, who is trying so hard to become prime minister, has chosen to play partisan games. To me, that’s very egregious: ‘foreign interference,”’ Trudeau said Wednesday at a public inquiry into foreign interference.

Prime Minister Trudeau went after Poièvre, accusing the Conservative Party leader of refusing to accept classified information and refusing to be briefed on confidential information about the party and some of its members.

Poièvre responded with a lengthy statement that included claims that Trudeau had lied under oath and called on the prime minister to release the names of the politicians.

Prime Minister Trudeau’s statement

In his pre-inquiry evidence, the prime minister said he had seen the names of Conservative MPs who were “involved in, or at high risk of, foreign interference, or for whom there is clear information about foreign interference”. He directed CSIS to pass that information on to Mr. Poièvre, but said CSIS could not do so without first giving him security clearance.

“The Conservative Party leader’s decision to obtain these names and not obtain the necessary permissions to protect the integrity of the party is baffling to me and completely lacking in common sense,” Trudeau added. .

Trudeau later said in cross-examination that he was aware that members of other parties, including his own, were vulnerable to foreign interference.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Wednesday that Conservative Leader Pierre Poièvre’s decision not to give a confidential briefing to the foreign interference inquiry means that no one in the Conservative Party “knows the names of these people and can’t take appropriate action.” ” means that.

Wesley Wolk, a national security expert at the Center for International Governance Innovation, said Trudeau’s testimony was not all that revealing.

“I think Prime Minister Trudeau made this sound a little more sensational than it actually was,” Wark told CBC News.

Wolk pointed to a report released in June by the National Security and Intelligence Congressional Committee (NSICOP), which found that some members of Congress had “semi-intelligent or tactful participation” in foreign interference activities. It was suggested that he was a person.

CSIS officials testify before investigation cast doubt on some of the conclusions of the NSICOP report. One CSIS official, in a private interview, specifically questioned the use of the word “witty.”

Mr Wark also said it was not clear to what extent anonymous MPs could be compromised, suggesting many MPs may not be aware of it.

“We’re talking about people who are seduced by foreign threat actors in ways that they may not fully understand themselves,” he said, adding that most foreign He pointed out that the actors were trying to “grow” politicians.

former CSIS directors Richard Fadden and Ward Elcock told CBC News. power and politics On Wednesday, Trudeau said in his testimony that perhaps he shouldn’t have taken such a partisan turn.

“When he made this accusation, he got really hyper-partisan and said things in language that couldn’t help but infuriate Conservative leaders. So that was his objective, and I think it worked. ” Fadden told host David Cochran.

“Did it advance the national security cause? Did it advance the interests of the investigation and the commissioner’s work? I’m not sure.”

Mr. Poilievre’s reaction

In a lengthy statement released in response to Trudeau’s testimony, Poièvre accused the prime minister of “lying.”

“My message to Justin Trudeau is to release the names of all MPs who cooperated with foreign interference,” Poilievre wrote. “But he won’t, because Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is doing what he always does: He’s lying.”

Poiivre has previously argued that his decision not to obtain national security clearance or briefings from intelligence agencies meant he would not be able to speak freely on foreign interference or criticize the government. I have defended it.

Mr. Fadden said that would not be the case.

“Just because you have a security clearance doesn’t mean you have to become a Carthusian monk and never speak,” he says. He also said Poilievre could choose to be briefed only on issues affecting his own party if he wanted to create a buffer in which he could criticize the government over foreign interference.

Two former CSIS chiefs react to the Prime Minister’s evidence at the Foreign Interference Inquiry and weigh in on whether federal party chiefs can receive confidential briefings on their behalf.

Poièvre said in a statement Wednesday that his chief of staff has received a confidential briefing.

“The government has never told me or my chief of staff that current or former Conservative MPs or candidates are knowingly participating in foreign interference,” he said. ” he said.

But Elcock said CSIS does not brief chiefs of staff on foreign interference issues involving individual members of Congress.

“What can the chief of staff do with that information?” Elcock said. “Because Mr. Poilievre does not have permission, the chief of staff cannot pass on information to him. And the chief of staff has no authority to do anything to or make decisions about members of Congress. There is no authority because he is not the Prime Minister.” ”

At Wednesday’s inquiry hearing, Nando de Luca, a lawyer representing the Conservative Party, said CSIS could use what it called “threat mitigation measures” to protect party members who could be compromised by foreign meddlers. He claimed that he might inform Mr. Poièvre.

But Faden said these threat mitigation measures are intended to alert politicians themselves to potential targets, and are not used to share sensitive information with party leaders.

“You can’t give sensitive information to people who don’t have security clearance. Can you play around with the margins and try to get people to think differently? Yes, but that’s not what we’re talking about.” he said.

Why doesn’t the government release the names?

Poiivre and the Conservative Party are calling on Prime Minister Trudeau to release the names of the MPs who are said to have been infected. They reiterated that demand on Wednesday.

However, law enforcement and national security agencies have made this point clear: sharing classified information is a crime.

RCMP Deputy Commissioner Mark Flynn told MPs on the Public Accounts Committee: “Anyone who divulges confidential information is equally subject to the law and clearly in this case the name is confidential at this time and is not publicly available. It would be a crime to disclose this.” In June.

When CBC News later asked Flynn if his name could be released in the House of Commons, where members enjoy certain legal protections, he suggested it could be a legal gray area.

“Given the complexity of parliamentary privilege, that’s a question you should ask legal experts,” Flynn said.

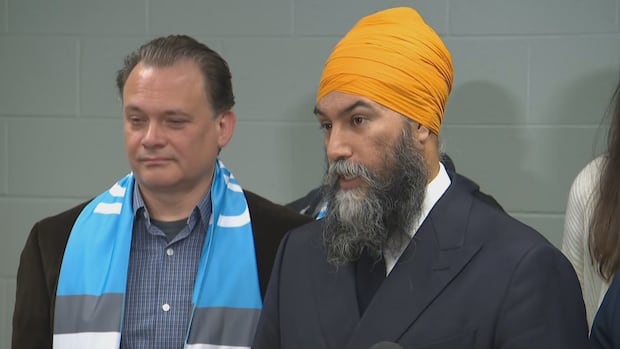

At a press conference in Toronto on Thursday, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh said the names of MPs involved in foreign interference should be released in a manner that respects national security.

Stephanie Carvin, a former CSIS national security analyst, said there are several reasons national security agencies don’t want their names released, including that it could jeopardize an ongoing investigation. stated the fact.

“We don’t want foreign governments to know how we collect information. That’s why we protect our sources and methods,” she said.

Mr. Elcock echoed Mr. Carvin’s argument.

“If the information comes from a secret wiretapping, the moment you reveal that you have the information, you alert the people you were communicating with that their communications were intercepted,” he told CBC News. It will happen,” he said.

“So what you’re actually revealing is not just the name; you’re also revealing the source and the method.”

Elcock and Carvin also pointed out that intelligence does not always equate to evidence that would hold up in court.

“The information could be hearsay, it could be a rumor, it could be something someone overheard without context,” Carbin said. She warned that simply publishing names without context could spark a “witch hunt.”

”[The named parliamentarians would] I can’t defend myself,” she said. “They may not know the context in which they were accused. They don’t know who their accuser is. And that’s really, really problematic in our system.”

In testimony Wednesday, Trudeau argued there are ways party leaders can use intelligence to reduce the risk of foreign interference in the party without giving away classified information. He suggested that compromised candidates could be secretly disqualified from running, while compromised politicians could be denied committee, ministerial or pundit roles.

“Depending on the severity of the allegation, we have a number of tools to respond,” Trudeau said.

Former Conservative Party leader Erin O’Toole told the committee last month: Considering expulsion of Conservative senator The senator was removed from the caucus over concerns that he was involved in foreign influence.

Mr. Carvin argued that a focus on releasing names may not help address the threat of foreign interference in Canadian politics.

“I can understand why people pay attention to it,” she said. “But this will not fix our democracy. What will fix our democracy is strong, healthy political parties that know better about the targets of threats against them.”