When humans eventually go to Mars, would it be better to do so in stages, by first building a so-called Mars orbiting base camp, as Lockheed Martin recently proposed? Or would it be better to use the Mars Direct strategy? Is it the best?

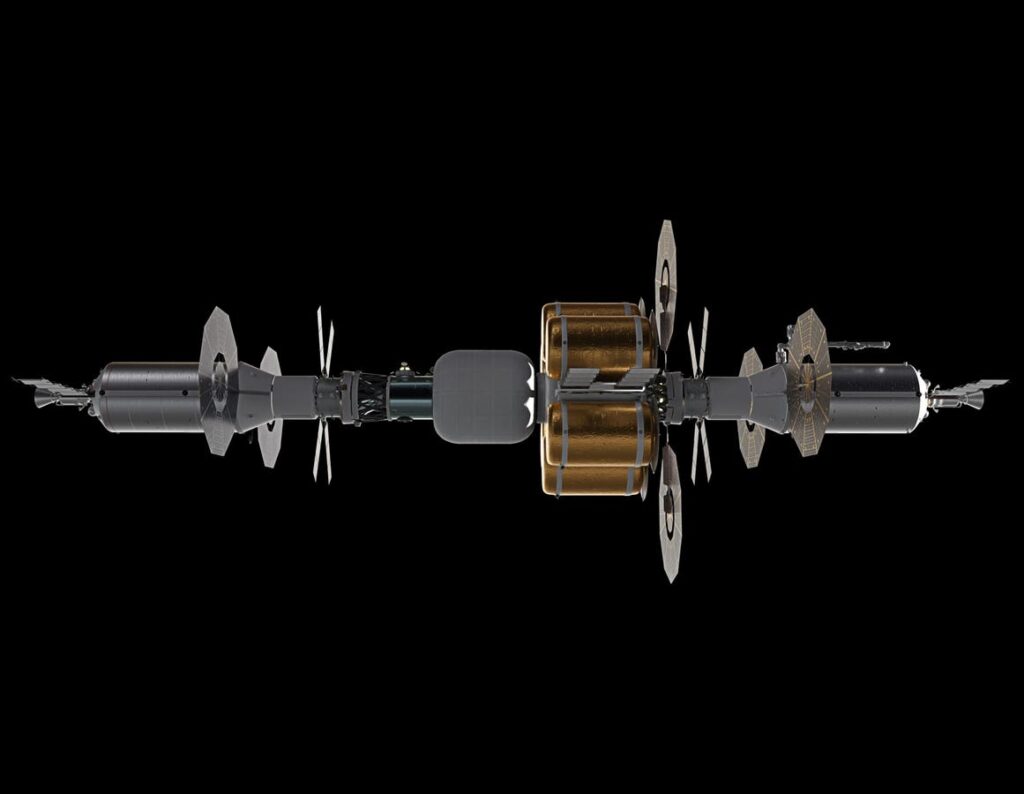

Mars Direct’s idea is to use existing technology to send astronauts directly to Mars via a spacecraft capable of interplanetary flight, landing on Mars, and returning home all at once. In contrast, the Mars Base Camp (MBC) concept envisions using the station as a base for multiple 14-day manned expeditions to Mars as well as excursions to Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos. It’s taking place.

Timothy Sichan, a space exploration architect and Lockheed Martin Fellow, said in an email that even if the Basecamp program begins, it will be about 10 years before it becomes a reality. Over the past five years, we have made great strides in technology development. We develop cryogenic and nuclear technologies in-house, and for that purpose we were selected to demonstrate nuclear thermal propulsion in space, he says.

Lockheed Martin said the orbiting station could perform remote robotic exploration of the Martian surface, including sample return. Then, once the manned ground mission is complete, the lander will return to the MBC as a single stage to the orbiting launch vehicle for refueling, Lockheed Martin said.

road to mars

You have two choices. One is to launch from Earth when the orbits of Mars and Earth are opposite, which occurs when Mars is closest to Earth. The second option occurs when Mars and Earth are furthest from each other in a so-called orbital alignment.

In a conjunction-class mission, the vehicle will leave Earth at an optimal time, head to Mars, and then wait for an optimal time to leave Mars, Shichan said. This would give the mission a total duration of about three years, of which about one year would be spent on Mars. Although the return leg isn’t the best time for an insurgency-class mission, it will ultimately only spend about a month on Mars, reducing the mission’s duration to about two years.

Mars advocate Robert Zubrin supports a conjunction-class mission.

They would enable a six-month journey each way to Mars, with a 18-year journey to the surface, said Robert Zubrin, an aerospace engineer and founder of the Mars Society and author of “The Mars Society.” Ta. In the case of MarsI was told this via email. If you want to do science on Mars, you need to stay long enough to do serious exploration, he says.

Lockheed Martin also supports long-duration conjunction-class missions.

Long-duration conjunction-class missions provide more science and exploration time, and require far less propellant, Shichan said. But if NASA chooses the opposition, we will support that choice, he says.

how to get there

Nuclear thermal propulsion streams hydrogen propellant through a high-temperature nuclear reactor that has both high thrust and high efficiency, Sichan said. Nuclear electric propulsion uses a nuclear reactor to generate electricity to power electric propulsion thrusters. This increases efficiency, but significantly reduces thrust. For human missions, nuclear thermal propulsion allows for shorter trajectories, he says.

What would happen if NASA changed the Artemis program’s plan to return to the moon?

Mars Basecamp is not contingent on Artemis’ success, but it will build on Artemis’ success to reduce risk and demonstrate capabilities, Cichan said.

The MBC includes both the Orion crew vehicle for return from Mars and the ascent and descent vehicles to the Martian surface.

Thanks to MBC broadcaster, the first mission will be an orbit-only mission to reduce risk and conduct groundbreaking remote robotic science on Mars and visit the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos. It’s possible, Sichan says. This allows more time to be spent on developing entry, landing and ascent systems. And the next step could be to use the orbital station as a base camp for 14-day ground missions to multiple locations during a single visit to Mars, he says.

Lockheed Martin and NASA are both interested in using water from the moon’s permanently shadowed craters or the Martian subsurface to generate spacecraft propellant.

According to Sichan, large-scale propellant production on the Moon could fuel not only transportation to Mars, but also vehicle transportation in Earth orbit and the Earth-Moon system. The technology could then be extended to the surface of Mars, he says.

Zubrin still supports a direct approach to Mars.

The goal of manned Mars exploration is scientific exploration, most importantly the search for life on Mars, something only human explorers on the Red Planet’s surface can do, Zubrin said. The question is, do we have a purpose-driven Mars program or a vendor-driven Mars program? Vendor-driven programs do things to spend money. A purposeful Mars program will explore Mars, he says.

The challenge is both technical and political.

The most optimistic period for any kind of human mission to the Red Planet currently spans a decade from the mid-2030s to the mid-2040s.

One of the challenges in gaining political support for Mars is the cost and long timeline of development, Chichan said. By doing the orbital mission first, he says, costs can be spread more evenly and a great mission can be achieved.

follow me twitter or linkedin. check out my Website or my other works here.