In the Arctic Ocean and North Atlantic, precipitation is increasingly falling as rain rather than snow.

The Arctic is known for its cold temperatures, which results in precipitation in the form of snow. But as temperatures rise, that snow is being replaced by rain. These changes could affect Arctic sea ice and weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere.

NASA Scientists studied rainfall trends in the Arctic Ocean and North Atlantic Ocean from 1980 to 2016 and found that the frequency of rainy days was increasing. They also found that the length of the annual rainy season had increased. The result is climate journal.

Increasing trends in precipitation and Arctic warming

The most dramatic changes occurred in the North Atlantic, where at the end of the 36-year study period there was an average of five more days of rain per decade than at the beginning. In the rest of the study area, i.e. in the central Arctic Ocean and its surrounding waters, on average 2 days of rain were added per decade.This happens because temperatures in the Arctic are rising 4x faster than any other part of the planet.

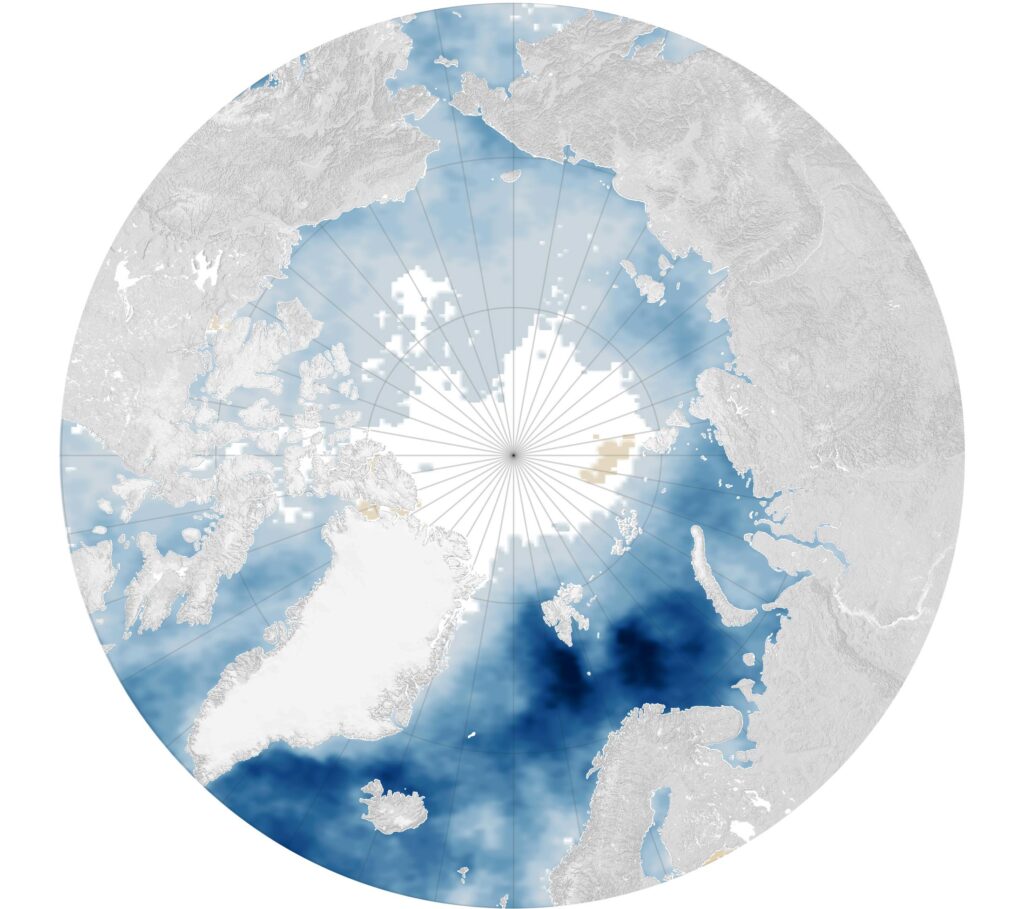

The map above shows changes in the number of rainy days per year, contributing to the increasing trend in Arctic rainfall over the past decade. It is based on. Modern Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2) is a global reanalysis product developed by NASA’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. The product takes in-situ and satellite observations, including from NASA’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) aboard the Aqua satellite, and uses them to recreate conditions that occur around the world.

Here, much of the North Atlantic Ocean is shown in dark blue. This indicates a significant increase in the number of rainy days per year (between 1980 and 2016) compared to the light blue region. The Barents Sea north of Norway and the Kara Sea north of Siberia are also shown in dark blue.

“The thing to keep in mind is that deep brown doesn’t really exist anywhere, so we’re never going to see a significant decrease in the number of wet days,” said Chelsea Parker, a weather and climate scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. I can’t do it,” he said. -Study author.

When temperatures drop below freezing, clouds are more likely to contain liquid that falls as rain rather than ice that falls as snow, said Lynette Boisvert, a cryosphere scientist at NASA Goddard and lead author of the study.

Effects of rainfall on Arctic ice and global weather

Rain falling on snow-covered sea ice can darken the surface, accelerate ice melting, and lead to further warming. This process is known as the ice-albedo feedback loop. The snow on sea ice acts as an insulator, reflecting solar radiation back into space and keeping the surface cool. Rain erodes this snow buffer.

“When it rains during the daylight hours, the surface becomes much darker because the snow is wet compared to a thick, dry snowpack with fresh snow. This wet snow surface begins to absorb more of the incoming solar radiation. “Yes,” Boisvert said. When snow melts, ponds form on top of the ice, darkening the surface and absorbing more solar radiation. This begins a continuous warming and melting loop.

Water vapor, on the other hand, drives its own feedback loop. As temperatures rise, the atmosphere can contain more water vapor. This water vapor acts as a heat-trapping greenhouse gas, warming the earth’s surface and contributing to the melting of snow and ice. This melting exposes the open ocean, causing evaporation and releasing more water vapor into the atmosphere.

Arctic feedback loops also affect other parts of the world. Changes in heat content in the Arctic can affect weather patterns further south. For example, Parker pointed to extreme temperature fluctuations in the United States and polar air masses that form over the North Pole and move south over North America.

“It all depends on how much climate change the Arctic is experiencing,” Parker said.

References: “Rainy Days in the Arctic” by Lynette N. Boisvert, Melinda A. Webster, Chelsea L. Parker, and Richard M. Forbes, September 8, 2023. climate journal.

DOI: 10.1175/JCLI-D-22-0428.1

Image by Wanmei Liang using data from NASA Earth Observatory Boisvert, L. other. (2023).