A team of researchers from multiple countries, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of Birmingham, has discovered a new way to determine whether an exoplanet is habitable or has the potential to be habitable.

The study, published Thursday in Nature Astronomy, shows that a planet with less carbon dioxide in its atmosphere than its neighbors means the presence of liquid water, a determining factor in habitability.

The researchers say this is likely because the carbon dioxide is dissolved in the ocean or “sequestered by planetary-scale biomass.”

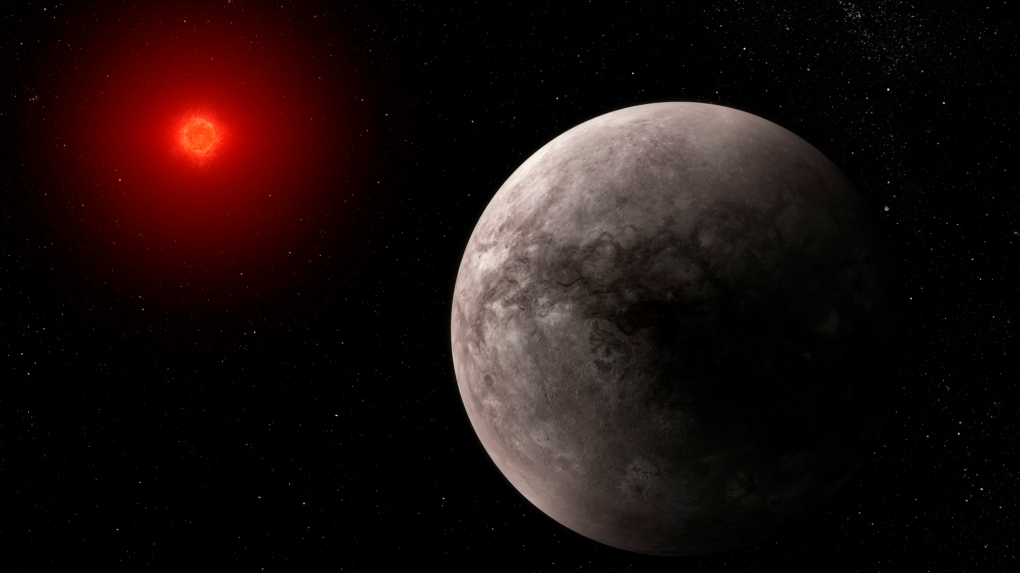

Scientists say habitability refers to whether an exoplanet can hold liquid water on its surface. Like Earth, this planet must be a certain distance from its star, an area known as the “habitable zone” or “Goldilocks zone.”

A news release accompanying the study states, “Planets that are too close to their star are too hot (such as Venus), planets that are too far away are too cold (such as Mars), but planets that are in the ‘habitable zone’ are just right.” It is being

The researchers say that until this discovery, there was no practical way to determine a planet’s habitability, although other scientists were making progress. The release notes that previous methods for determining the presence of liquid water on exoplanets included looking for starlight reflections, or “glows.”

However, the researchers added that this signature is difficult to detect with current existing technology.

Amaury Tryaud, professor of exoplanetology at the University of Birmingham in the UK and co-leader of the research team, said the new method could be used immediately.

“It is very easy to measure the amount of carbon dioxide in a planet’s atmosphere, because CO2 strongly absorbs infrared radiation, and the same property is responsible for the current increase in Earth’s temperature. .

Tryaud said scientists already know that Earth’s atmosphere was once made up mostly of carbon dioxide, until it dissolved into the oceans and allowed the planet to support life. Ta. He added that studying carbon dioxide on other planets could provide insight into the point at which carbon levels make a planet uninhabitable.

“For example, Venus and Earth are incredibly similar, but Venus’ atmosphere contains very high levels of carbon. There have been past climate tipping points that made Venus uninhabitable. It’s possible,” Triode said.

Julian de Witt, assistant professor of planetary science at MIT and co-leader of the study, said the new method could also be used for biosignatures, or evidence of biological processes.

“One clear sign of carbon consumption by biology is the release of oxygen. Oxygen can be transformed into ozone, and we found that ozone has a detectable signature right next to CO2. . Therefore, observing both carbon dioxide and ozone at the same time can tell us not only about habitability, but also about the presence of life on that planet,” de Witt said.

He also emphasized the importance of being able to check carbon dioxide levels on exoplanets with modern telescopes.

“Despite early hopes, most of our colleagues ultimately came to the conclusion that major telescopes like JWST (James Webb Space Telescope) cannot detect life on exoplanets. . Our research brings new hope,” said de Witt.

“By exploiting the signature of carbon dioxide, we can not only infer the presence of liquid water on distant planets, but also provide a path to identifying life itself.”