To understand why Canada has failed to criminally prosecute foreign collusion, old news reports from Washington provide a useful starting point.

In 1981, a Canadian correspondent ObservedWhen it comes to the use of security intelligence in policing, Canada and the United States have taken opposing paths.

The US increased production and Canada withdrew production, and the legacy of that era remains to this day. The ongoing Ottawa scandalAnd it’s unclear how much that will change. To be enacted soon Law.

Among Canadians, report Earlier this month, it was revealed that politicians had knowingly or unknowingly collaborated with foreign governments to receive campaign assistance and foreign donations.

What shocked me was that intelligence wasn’t even included. veteran A Canadian police officer who works closely with multiple U.S. government agencies has seen the night-and-day difference in police surveillance efforts in each country.

“It wasn’t a surprise to us,” said Scott McGregor, a former military and police intelligence officer and recent co-author of the study. One Book On Chinese interference in Canada: “This information has been around for years.”

WATCH | Reports say some MPs are helping foreign powers interfere in Canadian politics

A new parliamentary report paints a stark picture of foreign interference in Canadian politics and characterizes the government’s response as a “serious failure” that could affect the country for years to come.

“The problem of moving from information to evidence”

After the explosive parliamentary report, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released a lengthy statement announcing it was investigating – only to acknowledge in the next moment that the investigation had serious obstacles.

Firstly, police have limited access to information: the Royal Mounted Police admitted they were unaware of some of the details in the report.

There are some striking examples Page 29Indian agents allegedly claimed to have repeatedly transferred funds from India to Canadian politicians at all levels of government in exchange for political favours, such as pushing certain issues in Parliament. The report said the Canadian Security Intelligence Service had this information but did not provide it to the RCMP.

Both the report and the Mounties cited other obstacles. Even if police do see the information, using it in court is another, more complicated story.

Foreign Interference Act Just passed through Parliament’s Bill C-70 does not solve this problem, and two former heads of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service agree.

Ward Elcock and Richard Faden told CBC News that while parts of the bill may be helpful, attempts to prosecute would continue to run into unresolved constitutional issues.

“It can be deadly. [for criminal cases]” said Mr Elcock.

There’s even an industry term for the issue, said a former CSIS analyst, who described it as central to Canada’s struggles to prosecute national security cases.

“We call this the information-to-evidence problem, or I2E,” says Stephanie Carvin, now an associate professor in the Norman Paterson School of International Relations at Carleton University.

The turning point: 1981

Carbin sees the early 1980s as a turning point.

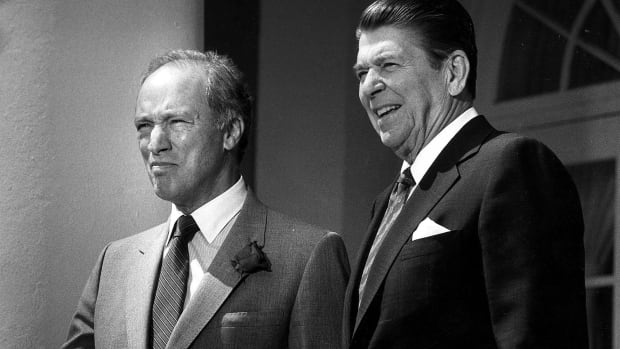

At the time, the United States was just emerging from the post-Watergate era, and intelligence agencies Scandal and disgraceSigned by President Ronald Reagan Presidential Decree and multiple International Security Command He encouraged intelligence agencies to cooperate with police.

Meanwhile, in Canada, inquiry It found that the RCMP engaged in unacceptable misconduct during their intelligence activities. Burning the Barnopening mail, breaking and entering, and stealing party membership data.

the government The era The reason why we turned a blind eye to such activities was 1970 Quebec terrorism crisis.

After the report was released, Pierre Trudeau’s government accepted its main recommendations and stripped the RCMP of its security intelligence role, handing it over to a new civilian agency, CSIS.

of Who led CSIS when it was founded? He freely admitted that he had no intelligence experience, which was seen as a positive.

“I’m a novice,” says Fred Gibson, a former low-profile civil servant. Said Toronto Star, 1981.

To this day, Canada does not have an independent foreign intelligence agency like the CIA or Britain’s MI6, and CSIS fulfills the domestic security role currently played by the FBI and Britain’s MI5.

Getting information back to the RCMP can be difficult.

WATCH | LeBlanc says federal government cannot release names of lawmakers in foreign interference report ‘by law’

Public Security Minister Dominique Leblanc said he takes very seriously the comments made by leaders who have read the unredacted NSICOP report, but wishes Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poirierbre had taken steps to obtain a security clearance so he could read the report. Leblanc also said that “by law” the government cannot release the names of lawmakers implicated in the document.

Intelligence agencies are rightly wary of leaking secrets: CSIS warrant applications, for example, can be as long as 50 pages and are full of details that could lead to the death of a source, Carvin said.

These applications are not publicly available, but if they are used in criminal cases they will need to be scrutinized in a more public setting.

“That’s where these cases fall apart” in court.

Lawyers have the right to know how a warrant was obtained and to challenge it on constitutional grounds. This right is: 1990 Supreme Court decision.

If CSIS cannot convince the court, the information obtained from the wiretap will be thrown out, Carvin said.

“CSIS would basically have to go to court and say, ‘Yes, we’ve got this.’ [our informant] “Sarah will be killed by the Russians,” Carbin said, “and that’s where these cases usually fall apart.”

She points out One failed caseCanadian military involved Shipbuilding Secrets It was to be sent to China. After years of controversy over intercepted communications from the Chinese embassy in Ottawa, the charges were dropped.

McGregor recalled that former police colleagues actively avoided accessing the information, which they believed was more likely to harm than help the case.

“I took information to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and they said, ‘Don’t say anything, you’re going to taint the case,'” McGregor said. “It’s not the only time that’s happened.”

He compares that to what he has seen from his international colleagues, who have worked frequently with Five Eyes civilian and military agencies during their careers in counterterrorism, narcotics, money laundering and piracy, and in roles with the Canadian Forces, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the British Columbia government, as well as in the Middle East and North America.

For example, if a local police force in the United States wants to wiretap a drug cartel, they would get funding for the operation from the Drug Enforcement Administration and report their findings to the Drug Enforcement Administration, which is under the jurisdiction of the Drug Enforcement Administration. Intelligence agencies.

“The United States understands intelligence,” McGregor said. “Canadian law enforcement doesn’t understand what intelligence is to the same extent as the United States.”

He said it was not surprising that U.S. intelligence agencies have led some of the most high-profile national security cases involving Canada.

Through the U.S. incident, Canadians learned details of the killings, allegedly ordered by the Indian government. Sikh nationalists In Canadian territory; Iranian Intelligence Agency Such as the alleged hiring of Canadians to carry out assassinations in the United States, and the crackdown on so-called Chinese police stations in New York. Several Canadian connection.

US intelligence powers have expanded since 9/11

The United States was also involved in the arrest of a top Royal Canadian Mounted Police official who was coordinating the police’s use of intelligence.

it is Washington State Arrest It unravelled a case against Cameron Ortiz, former chief of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s National Intelligence Coordination Centre. Ortiz is now 14 years in prison for leaking state secrets, On hold Appeal.

“A significant percentage of our cases start with the U.S. intelligence community,” Carbin said. “They have more agencies, more people, and they’re putting resources into this.”

Benjamin Witts, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and founder of the blog Lawfare, said the trend accelerated after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, which led to a series of changes to U.S. law.

Reforms since 2001 have expanded the use of intelligence in American police forces, Patriot Act, Follow-up legislation and related Court Cases. Researching the attack Communication between the foreign-focused intelligence agencies and the domestically-focused FBI was found to be poor, and subsequent reforms not only further integrated the activities of the two agencies but also made it easier to obtain surveillance warrants.

When Canada began public consultations on the current Bill C-70, the federal government He said it was under consideration Reforming the way intelligence information is used as criminal evidence.

But the bill, which passed the Senate and became law this week, does little on that front.

Criminalizing conspiracy

The C-70 has another role to play: Foreign agents must sign a public register in Canada, as they do in the United States, Britain and Australia.

In addition, it is a criminal offence punishable by life imprisonment to conspire with a foreign government, defined as a person engaging in deceptive conduct at the direction of a foreign government to influence Canada’s political process, such as legislation, party nominations or election platforms.

Carbin called the failure to resolve the so-called I2E issue a major disappointment.

“I understand why the RCMP are frustrated,” she said. “Unless this issue is resolved, we can make as many laws as we want, but we’re never going to be able to prosecute the way we should be.”

Faden, the former CSIS director, said he spent years trying to resolve the issue, and he hopes politicians can enact legislation that achieves the two conflicting goals of keeping details secret while allowing defendants to access information under their constitutional rights.

In Elcock’s view, the only way to resolve this issue is to amend the constitution or for the courts to establish new precedent.

Until then, he said, using intelligence to prosecute cases will remain more difficult in Canada than in allies such as the United States and Britain, which have different constitutional realities.

“We can’t just wish this problem away,” he said.