Science, the study of the natural world, evolved early, perhaps in its earliest forms long before modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

Characteristics would have been made possible by curiosity, imagination, and learning by observation about the natural world of the sky, weather cycles, flora and fauna, and the desire to understand everything.

This was coupled with a growth in symbolic thinking and language skills, which they used to share what they learned with their peers.

Since those early days, human understanding of nature has steadily evolved.

It is in the past two centuries that science has begun to develop with unprecedented breadth and speed, with important homages to the work of Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and others.

Major achievements of the 1800s included electromagnetism, thermodynamics, and Charles Darwin’s hypothesis in biology that species evolve in response to natural and, in some cases, sexual selection.

The pace accelerated in the 1900s with the arrival of Albert Einstein’s masterpiece, General Relativity, which linked mass to space-time.

If that wasn’t enough in a century, a new field emerged to explain the nature of atoms and subatomic particles and forces: quantum mechanics.

The latter proved to be highly predictive and accurate, supporting the development of digital computers and lasers, and how the sun’s nuclear fusion produces abundant energy.

Similar fusion-based methods currently under development offer the potential for nearly unlimited energy without producing dangerous nuclear or carbon waste.

In 1953, the structure of DNA was revealed, providing the basis for how genetic traits are passed from one generation to the next.

Over the next few decades, the mysteries of how cells maintain themselves, communicate with other cells, and make copies of themselves were solved, leading to the development of stem cells and the creation of mini-brains and other organ tissues. The path has been opened for use.

Without off-the-shelf messenger RNA technology, millions more people would have died from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The third theme is the world of digital computers and the realization by prophetic scientists in the 1950s that computers might one day be powerful enough to solve problems and questions that humans cannot solve.

Artificial intelligence offers many benefits, but like industrialization before it, it threatens many jobs today.

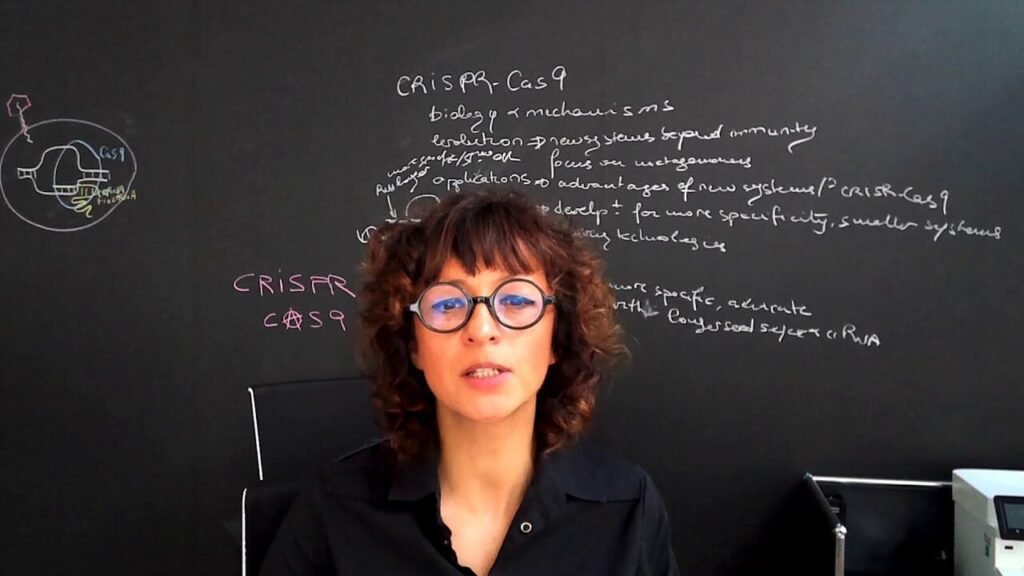

In 2020, Emmanuel Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna shared the Nobel Prize for developing a method to edit genes in all cells, including human cells.

The method, called CRISPR, provided an inexpensive and precise way to selectively silence genes and introduce them into the genomes of cells ranging from bacteria to humans, so much so that in less than 20 years, genetic The entire academic field has changed significantly.

The problem with such scientific advances is that they sometimes come with risks.

Eventually, scientists may be able to understand which genes underpin desirable physical, cognitive, or behavioral traits to give humans extraordinary powers.

Given that such efforts are currently underway and may soon become widespread, cracking down on them will likely prove impossible.

On the biology side, there is an ever-growing list of interesting technologies, such as using stem cells to create mini-versions of brains and embryos without parents or placenta.

There is a very real risk that within this century humans could overturn evolution by natural selection to evolution by designer technology, producing new versions of humans.

We’ve recently heard how threatening AI can be in China, where data on smartphones and facial recognition technology are used to track dissenters.

With the advent of quantum computers, the invasion of privacy will become even more powerful, and the privacy that exists on digital computers will disappear.

These are just some of the immediate threats posed by advances in science and engineering, some of which (such as quantum mechanics) were initially tackled innocently without thinking about their consequences.

The fear is that private companies and governments will soon have far more power than we could have imagined just a few years ago. And they will be largely unregulated.

Like the gods of Greek mythology, our species has acquired immense power without having the wisdom to manage that power responsibly.

Dr. William Brown is a professor of neurology at McMaster University. information health Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library series.