Is there anything there? Earth as seen by the Galileo spacecraft in 1990.Credit: NASA/JPL

Like many discoveries, it began by tickling a curiosity in the back of someone’s heart. That person was astronomer and communicator Carl Sagan. What tickled my fancy was the orbit of his NASA Galileo spacecraft, which launched in October 1989 and became the first to orbit Jupiter.The result was a paper Nature Thirty years ago this week, the way scientists thought about searching for life on other planets changed.

The opportunity arose from a tragic accident. In January 1986, about four years before Galileo’s launch, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff, killing seven people. NASA has canceled plans to send Galileo on a high-speed flight to Jupiter using a liquid-fueled rocket aboard another space shuttle. Instead, the spacecraft would be released more gently from the orbiting shuttle, giving mission engineers a gravitational boost to fling it around Venus and Earth and then on to Jupiter.

On December 8, 1990, Galileo was scheduled to skim past Earth, just 960 kilometers above the Earth’s surface. The tickling turned into an itch that Sagan had to scratch. He convinced NASA to point the spacecraft’s instruments at Earth. The title of the resulting paper was “The Search for Life on Earth from the Galileo Spacecraft.”1.

outside view

We are in the unique position of knowing that life exists on Earth. At a time when little was known about the environments in which life thrives, using your own home to test whether you could identify it remotely was an extraordinary proposition. “This is like his science fiction story in a paper,” said David Grinspoon, senior scientist for astrobiology strategy at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. “Imagine seeing Earth for the first time.”

It also happened at a time when the search for life elsewhere in the solar system was slowing down. U.S. and Soviet robotic exploration programs in the 1960s and 1970s revealed that Venus, once thought to be a haven for alien species, was hellishly hot beneath dense clouds of carbon dioxide. became.Mars intersected by astronomers’ imaginary “irrigation channels”2At first glance, it was a barren wasteland. In 1990, no one knew about the buried ocean on Jupiter’s moon Europa. This discovery was later achieved by Galileo.3 — or Saturn’s moon Enceladus, both now thought to be potential cradle for extraterrestrial life.

Importantly, Sagan and his collaborators took a deliberately agnostic approach to detecting life, said astrobiologist Lisa Kaltenegger, director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. he says. “Of course he wants to find life, as all scientists do,” she says. “But he said, let’s accept that wish and be even more careful, because we want to find it.” In the words of the paper, the existence of life was observed by Galileo. It was supposed to be a “hypothesis of last resort” to explain what happened.

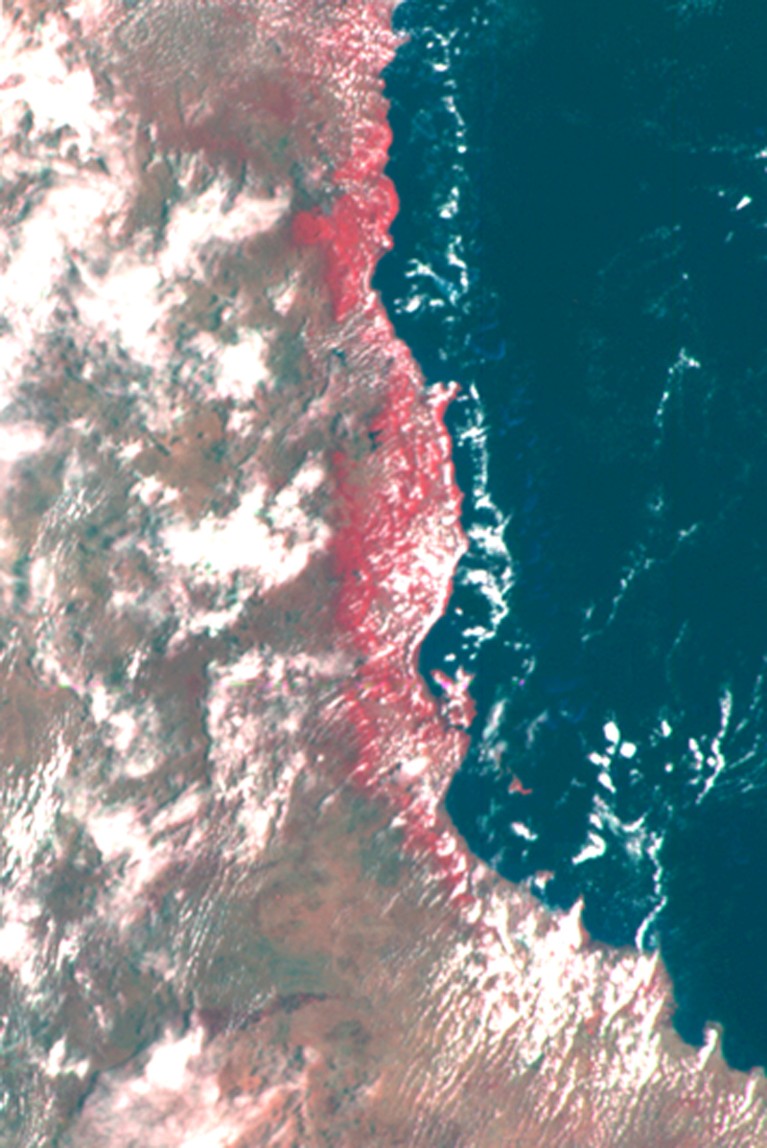

But even through this veil of skepticism, the spacecraft achieved results. High-resolution images of Australia and Antarctica taken during Galileo’s overflight showed no signs of civilization. Still, Galileo measured oxygen and methane in Earth’s atmosphere, and the ratio of the latter suggested an imbalance caused by life. It discovered sheer cliffs in the infrared spectrum of sunlight reflecting off the planet, a characteristic “red edge” that indicates the presence of vegetation. It then received radio transmissions originating from the surface, as if they had been artificially calibrated. “A strong case can be made that the signals are being generated by intelligent life on Earth,” Sagan’s team wrote, rather cheekily.

powerful control

Karl Ziemelis, current editor-in-chief of Physical Sciences Nature, I was in charge of the paper as a new editor. He has stated that this paper remains one of his favorites, as well as one of his most difficult to get into. Editorial approval for this paper was far from unanimous. Because it clearly wasn’t saying anything new. But Ziemeris says that was largely beside the point. “This was an incredibly powerful controlled experiment into something that a lot of people weren’t paying attention to at the time,” he says.

“We knew the answer, but the way we thought about the answer had changed a lot,” Kaltenegger says. Only by taking a step back and thinking about Earth like any other planet, perhaps one that may or may not harbor life, can we understand our place in the universe and other places. She says it can give you a real perspective on the possibility of life.

There are no traces of civilization in Australia.Credit: NASA/JPL

Considering developments since Galileo’s flight, it has taken on new importance. In 1990, there were no known planets orbiting stars other than the Sun. It took another two years before astronomers finally reported the first “exoplanet” orbiting a spinning dead star known as a pulsar.FourIt took another three years until it was discovered.Five The first star is around a Sun-like star, 51 Pegasi. Currently, scientists know of more than 5,500 exoplanets, but very few resemble any planet in our solar system. They range from “super-Earths” with strange geology and “mini-Neptunes” with gaseous atmospheres to “hot Jupiters,” giant planets that swirl near glowing stars.

When Sagan and his colleagues aimed Galileo at Earth, they invented a scientific framework for searching for signs of life on these other worlds. Since then, this framework has pervaded every exploration of such biosignatures. Kaltenegger still passes Sagan’s paper on to his students and teaches them how to do it. She tells them that life is the last inference drawn, not the first, when one sees something unusual on another planet. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

The perfect combination for life

This lesson could not be more important today, as scientists stand on the precipice of potentially revolutionary and perhaps monumentally disruptive discoveries made by the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). . The telescope has just begun remotely probing the atmospheres of dozens of exoplanets, looking for the same kind of chemical imbalances that Galileo found in Earth’s atmosphere. Early hints of biosignatures that may lead scientists and the public astray are already emerging.

For example, JWST sniffed out methane in the atmosphere of at least one planet. That gas is a strong signature of life on Earth, but it can also come from volcanoes without requiring life. Oxygen has attracted the attention of scientists because it is mostly produced by life forms on Earth, but it can also be formed when light breaks down molecules of water and carbon dioxide. Finding the right combination of methane and oxygen could indicate the existence of life on another planet, but that world would need to be located in a temperate zone that’s neither too hot nor too cold. Finding the right combination of life-sustaining ingredients in a life-friendly environment is difficult, Kaltenegger said.

The same is true for other interesting mixtures of atmospheric gases. Just last month, astronomers studying JWST data reported finding methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a large exoplanet called K2-18 b. They suggested that the planet may have oceans of water covering its surface and hinted at intriguing detections of dimethyl sulfide, a compound that comes from phytoplankton and other organisms on Earth.6.

The headlines were all over the place, with news articles floating around about possible signs of life on K2-18 b. Never mind that the presence of dimethyl sulfide is reported with low confidence and requires further verification. It’s not like water hasn’t actually been detected on Earth either. And even if water were present, it could be deep enough in the ocean to thwart all geological activity that could sustain a temperate atmosphere.

build evidence

Such challenges led former NASA chief scientist Jim Green to propose a framework in 2021 for how to report evidence of extraterrestrial life.7. For example, he argues that a progressive scale from 1 to 7 could help convey the level of evidence for life in a particular discovery. Maybe you’re receiving signals that could be due to biological activity. It’s just something on the scale. To reach Level 7 and prove a true discovery of extraterrestrial life, many more steps must be taken, such as ruling out contamination and obtaining independent evidence of the strength of the signal. there is.

It can take a long time. Telescopes may sniff out interesting molecules, and scientists will debate them. Another telescope may be built to elucidate the observational situation. Each brick of evidence is laid on top of another, and each layer of mortar must be mixed with the arguments, skepticism, and agnosticism of so many scientists. And it is the assumption that life on other worlds is similar to life on Earth, an assumption underlying the conclusions drawn from Galileo’s observations. “The uncertainty could last for years or even decades,” Grinspoon said. Sagan, who died in 1996, would have loved it.

The same year that Galileo observed Earth, Sagan persuaded NASA to point another spacecraft in a direction that NASA had not planned. As Voyager 1 passed Neptune on its way out of the solar system, it returned its camera to Earth and photographed a tiny dot glowing in the sun’s rays.this is Iconic pale blue dot image Sagan began to reflect on this in his 1994 book. pale blue dot: “This is it. That’s home. That’s who we are.”

Its fragile, glowing pixels have reshaped the way humanity visualizes its place in the universe. Kaltenegger said the same goes for using Galileo to search for life on Earth. “This is a way to use pale blue dots to provide a template for searching for life on other planets.”