Sign up for the Unity Health Toronto newsletter. Monthly updates on the latest news, stories, patient testimonials, and research emailed directly to subscribers.If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can subscribe by click here.

When Crystal Ellis arrived at the hospital in July, her left leg had swollen to nearly twice its size.

“The pain was from my legs to my stomach,” she explains. “My stomach was so swollen I could barely walk.”

This was not her first experience with these symptoms. Ms. Ellis had a blood clot in one of her major veins that runs from her left leg to her abdomen in 2014. This condition, called deep vein thrombosis or DVT, occurs when a major vein from your leg or arm becomes blocked, stopping blood from circulating. It is returned to the heart where it is reoxygenated and recirculated.

An estimated 45,000 Canadians are affected by DVT each year. Common symptoms include swelling, pain, redness, and warmth in the affected area. DVT is usually treated with anticoagulants (commonly known as blood thinners).

One of the risks of DVT is that the blood clot can travel to other parts of the body. In 2014, Ellis also suffered a pulmonary embolism, in which a blood clot traveled to his right lung. She ended up staying in the hospital for more than a month for treatment and recovery.

At the time, Ellis had a stent inserted into a vein in his left leg as part of his DVT treatment. A stent is a small mesh tube that is placed inside a vein to keep the vein open. In July of this year, Ellis was experiencing severe swelling and pain because a blood clot had formed and hardened inside the stent, completely blocking it. She was taken by ambulance to St. Michael’s Hospital, where the interventional radiology team did their best to remove and open the stent.

The hematology team at St. Michael’s continued to monitor Ellis, and although the treatments at St. Michael’s were effective, he still suffered from swelling and pain in his left leg.

“I can’t run like I used to. I have a 7-year-old and I can’t play with him at the park,” Ellis says of the impact of DVT on her daily life. “Going up and down the stairs is a challenge for me. The building I live in has 25 floors. There are three elevators, but the elevators often don’t work.”

Around this time, the interventional radiology team was discussing the introduction of a new device called the RevCore thrombectomy catheter. The new device features an adjustable metal coring element that scrapes away clots that form and harden within the stent.

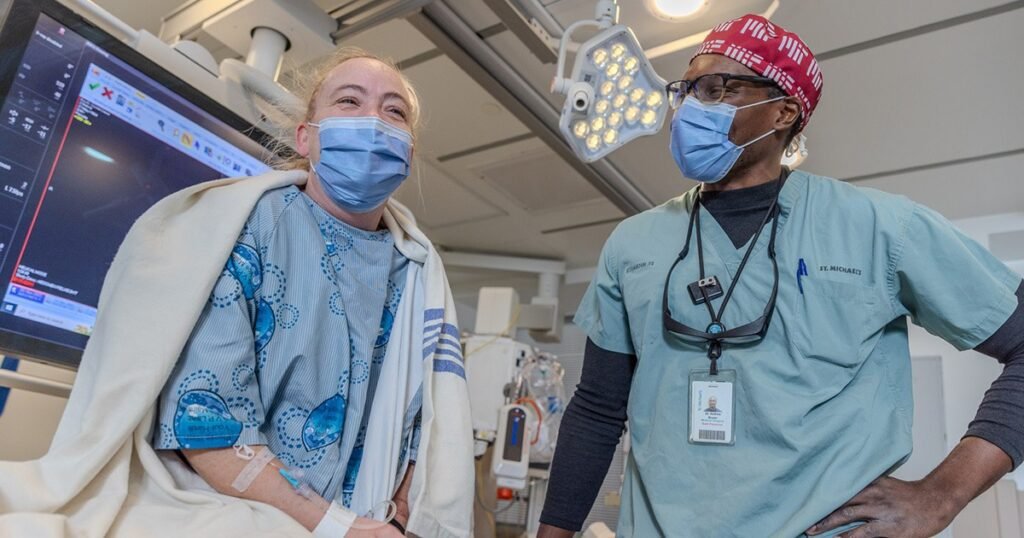

Ellis is the first patient in Canada to be treated with the device.

“Without these new types of tools, our ability to treat clogged stents is limited,” says Dr. Andrew Brown, an interventional radiologist at St. Michael’s. “Essentially, these patients needed to manage their pain and reduced mobility in the best way possible.”

Interventional radiology is a medical specialty in which physicians use imaging tools such as ultrasound, CT scans, and X-rays to provide image-based, minimally invasive treatments and care.

During surgery in late November, Brown inserted the device into a vein behind Ellis’ knee. Once the device arrived at the stent, he increased the diameter of the coring element and rotated it in his hands to scrape away the blockage inside the stent. Throughout the procedure, he and his team used his X-rays and ultrasound to help guide them.

Ellis went home the day of surgery and has regular visits with the interventional radiology team.

For Brown, using the new device achieved exactly what he wanted.

“I was very happy with the results. Now I have to let the medicine work,” Brown said of the blood thinners Ellis continues to take.

“Immediately after surgery, the area where the clot was scraped becomes prothrombotic, meaning it is looking for platelets and clotting factors to grab the clot and form more clots,” Brown explains. . “After a certain period of time, the drug goes dormant and the patient can stop taking the medication.”

“Monitoring is the big key,” Brown says. “Sometimes it’s just a relief for the patient, but sometimes it’s actually really important because you start to see that some of the stent looks like it’s narrowing again.”

In the months following the procedure, Ellis noticed significant improvement.

“Before, just going to another room would cause my legs to swell up and be very painful,” Ellis says. “There’s still some swelling, but unless you walk long distances, the pain is minimal.”

Addressing gaps in deep vein thrombosis treatment

Adding this new device to the toolbox is an exciting development for Brown and the interventional radiology team at St. Michael’s University.

“The majority of people I meet are in their 20s, 30s and early 40s,” Brown says. “For them, not being able to exercise, not being able to walk up the stairs without pain or shortness of breath is a significant disability. “We’ve tried our best, but there’s nothing left to offer you. It doesn’t feel good to have to tell a patient, “No.” ”

It also helps address a gap that Brown knows has long existed among patients. He detailed one patient in particular at the hospital where he worked before coming to St. Michael’s. She had a DVT that blocked a large vein in her abdomen, causing swelling and inflammation in both her legs. He and her colleagues did everything they could to help her, but the tools and options available at the time weren’t enough.

“She ended up getting sick and passing away, so I still think of her often,” Brown said. “I wasn’t able to help her at the time, but the opportunity to bring something new to St. Michael’s that could help patients like her is very important to me.”

These new innovations complement our ongoing efforts to create a multidisciplinary approach to DVT care that sets St. Michael’s Hospital apart among its peers.

“To my knowledge, this is the only location in the state where hematology, vascular surgery, interventional radiology, and emergency medicine specialists bring their resources and expertise to work with DVT patients,” Brown explained. do. “Some cases can be very complex, so it takes a team effort to get this right.”

Story by Robin Cox

Photo: Yuri Markov