× close

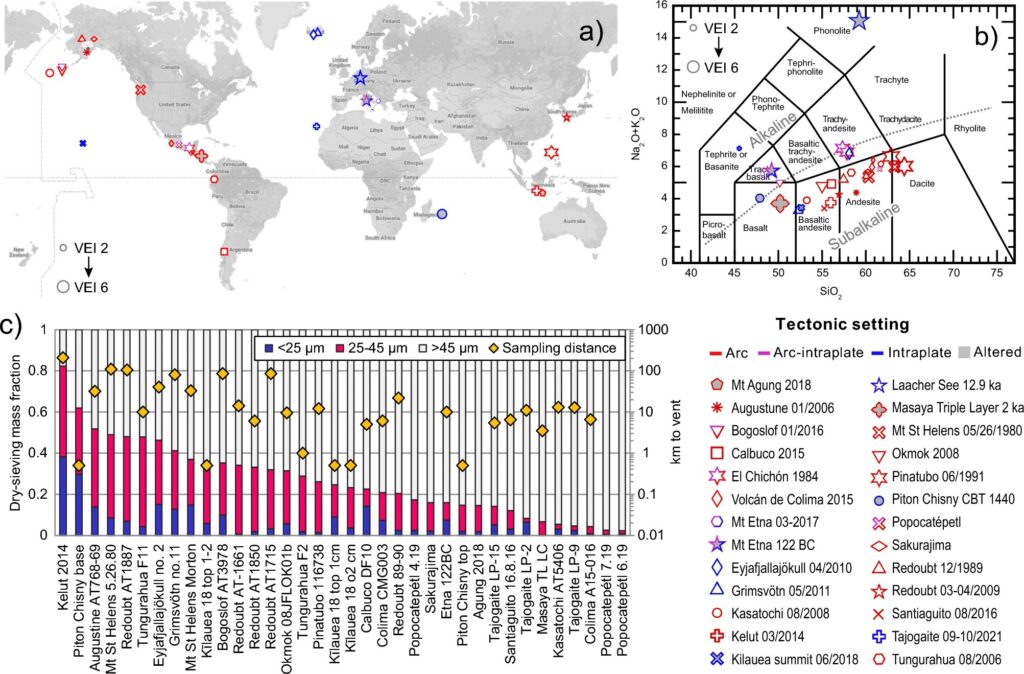

Global eruption locations and bulk chemistry. (be) Locations of the volcanoes that produced the volcanic ash used in this study (see Supplementary Table 1 for details) Symbol size is scaled to the Eruption Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). (b) Total alkali to silica (TAS) diagram34 The bulk chemistry obtained from the literature of the research samples is shown in weight percent of oxides. Compiled data and references are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 and 7. Multiple data points summarize the range of eruption chemistry in which the ejected material was heterogeneous. All symbols and colors in panels a–b follow the legend. Bicolored symbols indicate more complex arc-intraplate structural settings, and the bottom right color indicates the primary structural settings assigned for calculations and linear regression. (c) Dry sieving fractions for the particle size range used in the study are shown as stacked bars in order of total < 45 µm fractions. The golden diamond indicates the sampling distance from the crater. credit: scientific report (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-41412-x

Volcanic ash is no ordinary dust. It is injected into the atmosphere and rises into the stratosphere, affecting the climate, crushing roads, and clogging jet engines.

To bridge the knowledge gap between volcanologists and atmospheric scientists working on climate change and observing global systems, researchers at Cornell University have analyzed the Characteristics of volcanic ash samples were investigated. This research is helping scientists understand how these tiny substances, measured in microns and nanometers, play a major role in the atmosphere.

the work, “fine volcanic ash phase‘ was published on September 21st. scientific report.

“Large volcanic eruptions can have measurable effects on climate for years or even decades,” said lead author Adrian Hornby, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. Ta. “The dispersion and transport of fine volcanic ash, and its interaction with the Earth, has implications for a variety of fields, from atmospheric science and climate modeling to environmental research and even public health.”

Volcanoes can be formed by hot spots deep in the Earth’s mantle, like the volcanoes in Hawaii, or they can form in subduction zones where two plates collide. However, each has a different fingerprint-like composition and can pose different environmental problems that create complex problems for the planet.

Volcanic ash is a complex particulate material formed from fragments of magma that is injected into the atmosphere during explosive volcanic eruptions, Hornby said.

“The ash contains some minerals, silicate glasses and pores, but the composition and properties expected to be produced in an eruption are not well defined,” Hornby said. “This also applies to the fine volcanic ash that is widely transported in the atmosphere, with far-reaching impacts on Earth systems, infrastructure, and human health.”

Due to a lack of data, the scientific community relied on rough approximations and poor models of ash composition. Now, the Cornell University group has collected samples from 40 eruptions characterized by their size and tectonic background to provide a better and more comprehensive data set. They focused on volcanic ash particles smaller than 45 microns, which is important because atmospheric winds can transport volcanic ash and have widespread effects.

They found that the composition of volcanic ash varies widely depending on particle size, crustal environment, and chemistry. As the particle size became finer, the percentage of crystalline silica (which can cause health problems and lung cancer if inhaled) and salt increased, and the glass and iron oxide components decreased.

The sifted samples included Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines (1991), Mount St. Helens in Washington state (1980), Mount Etna in Italy (122 BC), and La Palma in the Canary Islands, Spain (2021). were collected from 23 volcanoes, including The group uses X-ray diffraction to detect the atomic structure of materials, uses improved methods to identify and measure mineral-to-glass proportions, and scanning electron microscopy to identify phases, determine morphology and The organization was evaluated.

The mineral content of the samples varies widely. At Pinatubo, feldspar (a group of aluminosilicate minerals abundant from the Earth’s crust) and amphibole (an important mineral in volcanic explosions) are produced in large quantities, and quartz has undergone significant melt evolution, including through fractional crystallization. showed evidence of. Pre-eruption process.

At the other extreme, the 2021 tahogite eruption on the Spanish Canary Island of La Palma, the majority of the mineral load was feldspar, clinopyroxene, and olivine. The last one was a mineral characteristic of primitive melts with little evolution from mantle sources.

Hornby said that in samples taken from tajogite in 2021, the average amount of glass decreased from 50% to 35%, but the proportion of dense iron-bearing minerals increased from 35% to 50%. That’s what it means. In all cases, salt increased with finer particles.

“We saw a significant increase in salinity in the finer-grained ash,” said lead author Esteban Gazelle, the Charles N. Mellows Professor of Engineering. “This is important because salt dissolves easily. When fine ash reaches the ocean, the salt dissolves first. You don’t want to inhale it because it will react with your lungs.”

Volcanic ash is the most interdisciplinary aspect of volcanic activity due to its large production, atmospheric transport, and deposition in all known ecosystems. “Our study is the first to better constrain the mineral and glass composition and density of volcanic ash, which atmospheric scientists need to investigate volcanic ash transport and better understand its impact on the Earth system.” data-driven resources,” said Gazelle, who is also an academic researcher. Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

Ash density is controlled by mineral content. “We were able to get pretty good density estimates from the minerals and iron oxides, regardless of the size or origin of the magma,” Hornby said.

This atmospheric ash can travel long distances and affect the climate and ecosystems of other continents far from the volcano. “Atmospheric scientists have ignored the effects of volcanic ash on climate and biogeochemistry,” said co-senior author Natalie Mahowald, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering. “This study finally provides us with the data to estimate the impact.”

For more information:

Adrian Hornby et al., Fine Volcanic Ash Phases; scientific report (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-41412-x